Murphy – Midway through the Vietnam War, Richard Ferris received a Christmas present that would change his life permanently.

On that day 55 years ago, Ferris received word from President Lyndon B. Johnson.

“Most Americans don’t know that during wartime, the Marines Corps drafts,” Ferris said of his inscription into the U.S. Marines. “So when we got our draft notice, my best friend growing

up and I both got our greetings from the president on Christmas Eve of 1965. Now my friend got his and

I didn’t get mine, only because my mother got it and hid it, then gave it to me the day after Christmas.”

Ferris and his friend would enlist on Jan. 12, 1966. They ended up sticking together through boot camp in California and all the way until the pair arrived in Vietnam.

“I went into Third Battalion, Fourth Marines, and he went into First Battalion, Fourth Marines,” Ferris said. “And we saw each other maybe six months later out in the field. We both had agreed that it was much better that we got separated because we weren’t constantly talking about home.”

Gunfire in foxhole

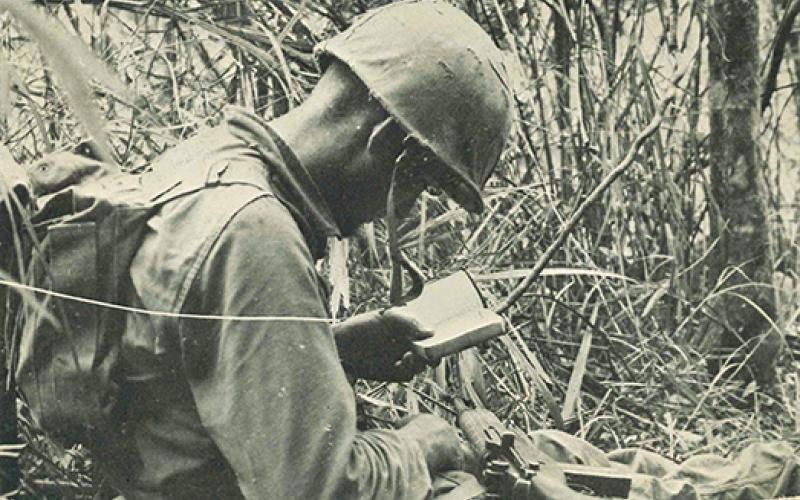

On his first day out in the fields of Vietnam, just after helicopters dropped off him and his company, Ferris was immediately thrust into the conflict as gunfire erupted around him. Ferris found himself on the ground in a foxhole trying to avoid the falling helicopters, at one point running out of his foxhole to avoid a falling chopper he was sure would land on him.

Miraculous, the helicopter suddenly moved in the opposite direction at the last second, which Ferris and the rest of the men on the ground suspected was the last-ditch effort of the pilot to avoid crushing the men underneath him.

“On my first day out in the field, when the helicopters dropped us off, I didn’t have a clue of anything,”

Ferris said of his first day in the field. “Well, right away we got shot at, four helicopters went down and, of course, when they got shot they lost control and they collided.

“I wasn’t even in the field for an hour and that was Operation Hastings, which had been the biggest wartime battle at the time.”

Feeling comes true

After a few months of various conflicts, including Operation Prairie, Ferris and his squad-mates were talking during a break in the action when he got a strange premonition.

“It was December, around Christmastime, and I was talking with some of the guys in the squad,” Ferris said. “And I said to them, ‘You guys, something is going to happen to me. I don’t know when, but it’s going to happen – and I don’t mean the normal fear that we all carry, this is different.’”

A few days later, Ferris’ feeling rang true when he and his company came under heavy mortar fire.

“A couple of days later we had a mortar attack, and it was terrible,” Ferris said. “Someone hollered, ‘Incoming,’ and at that time, I was chosen to go down the line and give out the new password, and because I was doing that I wasn’t near my foxhole. So when mortars started crashing all over the place of course I took off running to get to the foxhole and my rifle.

“Well, I tripped over one of the tent sticks in the ground, and had I not tripped over that I would’ve been one step closer to the mortar that went off. And I got hit pretty bad.”

The mortar littered Ferris’ body with shrapnel. That caused him to lose so much blood the medics treating him were not sure he was going to make it, to the point where they read him his last rites.

Awake in hospital

Ferris woke up four days later in De Nang, Vietnam, at a safe military hospital with almost no memory of the days between his wounding and eventual awakening in the hospital.

“I was in and out because of shock, but one of the things that was scary to me was that the Corpsman was there and he says, ‘This guy goes next, he’s No. 1,’ ” Ferris said of what little he remembers of his transportation from the battlefield to the hospital. “And he was talking about me. I had lost so much blood that they had to cut down at my ankle to get to a vein, I wasn’t expected to make it.”

Later on, Ferris was

told his dog tags had been found near where he was wounded with a hole in them, the metal saving him from yet another piece of shrapnel. The news of Ferris’ wounding would reach his family on New Year’s Day, catching his family by surprise.

Ferris’ younger brother, who enlisted after graduating from high school, was home on leave before going to Vietnam so when his mother saw uniformed men coming up to the door, she suspected it was just a few of his brother’s friends coming by.

“I have seven holes in my body that weren’t there before, but I’ve got both arms, both legs and I can

do just about anything else that anyone does,” Ferris said, reflecting on his wounds.

What was it for?

Soon after, Ferris would be sent out onto a hospital ship, the USS Repose, where he would recover from his injuries before once again being sent back to Vietnam, which he couldn’t believe.

He wouldn’t be there very long, as his company was sent back to Okinawa, Japan, to regroup, where Ferris was left to serve out the remaining three months of his tour in safety working as a janitor in a pharmacy.

Ferris would leave the service in January 1968. He couldn’t stand the cold of Michigan anymore after dealing with the weather in Vietnam, so he moved to Florida shortly after returning to the United States before eventually finding his way to Cherokee County, where he is active in veterans issues and a member of MountainView Church.

“The saddest part is that we didn’t win the war,” Ferris said of his time spent in Vietnam. “So what was it all for?”